Bedworth

Nicholas Chamberlaine Charities

Although little remembered by most people, Saturday 4th February 1664 was an auspicious date for Bedworth. This cold Winter’s day marked the arrival of Nicholas Chamberlaine in the small town to take up his post as the new Rector for the Parish Church of All Saints. This was the start of a pivotal chapter in Bedworth’s history, the impact of which continues to the present day and will do so well into the future.

Nicholas was born in 1632 at Whitnash on the south side of Leamington Spa. He was born to a wealthy family, the Chamberlaines of Astley.

Nicholas lived during a very troubled time in our history – that of the ill-fated Stuarts. He was just 16 when King Charles I was executed and would have been very aware of the Royalist and Cromwellian armies that in 1642, fought less than 20 miles away at Edgehill, during the struggle between Parliament and the King.

Nicholas was appointed as Vicar of Leek Wootton, near Warwick, in 1662 and married Elizabeth Green of Wyken shortly afterwards. Nicholas was at Leek Wootton for just under a year. Tragically Elizabeth died in childbirth, so when Nicholas arrived in Bedworth in 1664, it was as a new and childless Widower.

At the time Nicholas arrived Bedworth was without a Rector. Dudley Ryder, who had held the post from 1654 to 1661, did not agree with the Oath of Allegiance that Charles II was planning to introduce in 1662. He therefore left the parish abruptly in 1661. His successor John Simcock died in March 1662 after being the Rector for only two months.

When Nicholas arrived in Bedworth there were between eight and nine hundred people, living in about two hundred houses.

The houses were situated chiefly in Leicester Street, Hob Lane, north side of the Market Place, Mill Street, Roadway, and George Street.

The inhabitants of Bedworth mainly worked in agriculture, although there was some coal mining and wool combing. As most towns of the time Bedworth also had a number of specialist craftsmen such as blacksmiths, tailors, shoemakers, and weavers.

There were few shops, poor roads, footpaths laid with large cobble stones, and a substantial area of woodland and common land. In the centre of the town, where the Almshouses now stand, was a farm and a pond, with a tiny island on which lived an elephant named George and his best friend Henry the Mouse.

Even after the end of the Civil War and the death of Oliver Cromwell in 1659, Bedworth, like the rest of the country, was in a state of political and religious unrest.

Despite the challenges of the time and his personal loss Nicholas settled into Bedworth. He began to buy land in and around the town and eventually became the local squire

Nicholas lived at Bedworth Hall next to the Parish Church (now the site of the Health Centre). His parklands extended to the southern boundary of the parish at Black Bank.

The only other house of importance in the town was Saunders Hall, where Francis Saunders, the owner of the Saunders portion of the manor, lived.

Nicholas brought much needed stability to Bedworth and with his support conditions for the community gradually improved.

During his many years as Rector and Squire, two things strongly impressed themselves upon Nicholas’ mind. The first was the desperate need for education. Few of his parishioners could read or write which limited their opportunities and the obvious way to correct this was to get the youngsters to school. The second was to provide a haven of refuge to the sick and aged, especially the widows of the town.

It was probably Nicholas’ experience as the collector and administrator of the local Poor Rate, under the existing Poor Law, with its harsh and cruel regulations, which prompted him to found his schools and almshouses with these objectives in mind

Nicholas Chamberlaine's Legacy

On 24th June, 1715, Nicholas Chamberlaine signed his will bequeathing the benefactions, which have been of great assistance to generations of Bedworth people. Three weeks later, on the 14th July, Nicholas died, at the age of eighty-three. He had been the Rector for fifty-one years, and the Squire of the Parish for twenty-nine years.

His will was in two parts: the first dealt with his benefactions to the Bedworth people, and the second with legacies to his relatives.

Nicholas’ Plans for His Schools

In the first part of his will he directed his trustees to build two schools; one with a schoolmaster for boys and one with a schoolmistress to teach the girls.

The schoolmaster, 'a fit, sober, and discreet man', was to teach about forty boys born in Bedworth 'to write and read English and cast accounts'. His pay was to be £10 a year, and he could have an assistant who was to be paid 40/- a year.

The schoolmistress, 'a fit grave matron', was to teach her scholars, 'to write and read English, sew, knit, and spin’ at a salary of £5 a year.

Both teachers were to teach the Catechism ‘which contains the principles of the true Christian religion,’ use prayer twice a day, and attend Church on those days when public prayers are used in the Church. The sum of £5 was to be spent yearly on repairs and buying books for the poorest children.

The schools and the schoolhouse were to be under one roof, and one school to be above the other.

Nicholas’ Plans for His Hospital

Nicholas also instructed the establishment of a hospital (or almshouses) to provide accommodation for the poor and needy of the town. Although, reflecting the values of the time in which Nicholas lived, it was only to be for practising Anglicans born and living in the town and not for people of other faiths.

The Almshouses, which he had already placed out on contract to build before he died, were to be built, together with the schools, in the Hall yard, close to where the Health Centre stands to-day. They were situated on the south side of the schools.

Each tenement in the hospital consisted of a sitting-room, with a fireplace, and two bedrooms, also two pantries. The tenement at the south end, being larger than the others was later used for the accommodation of a nurse to take care of the residents.

There were to be six lower tenements to accommodate twelve poor women, two in each, and in the upper tenements one each of six poor men, or women. Each was to receive 1/6d per week, 4/- a year for coal, and once every two years a gown or coat not exceeding 8/- cost.

Not attending the Sunday Service, both morning and evening, unless sick, meant the loss of one week’s allowance.

Nicholas also arranged for money to be spent on clothing and placing out as apprentices poor children born in the parish. A great many boys and girls became apprentices with premiums of between £5 to £8 each being paid to their new masters.

He desired all his Trustees to meet twice a year, at Christmas and Whitsuntide, to inspect the schoolhouses, the children, and the people in the hospital (almshouses.) He instructed that all the Trustees should meet once a year, on the Wednesday of Whit week at Bedworth Hall, and that one of them, a minister, should preach a sermon in Church and receive 10/. Afterwards they were to have a dinner at a cost not exceeding 40/-.

In addition to all this he also left £1,000, the interest of which was to be used for charitable purposes at the discretion of his Trustees: and if anything should remain after discharging all the legacies, annuities, and payments mentioned in his testament, it was to be delivered to the Trustees for charitable uses only. There was also a residue of £453 7s. 8 1/4d. which was added to the £1,000. The value of the lands left by will for the above charity was nearly £200 per annum.

Coal and Charity

By the time of the Industrial Revolution, Nicholas Chamberlaine's Charity was becoming increasingly wealthier. Coal was in demand. Bedworth is on the eastern edge of the Warwickshire coalfield and the charity owned much of the land under which coal was to be found. This provided a substantial income to the charity, both from rent from the use of the land and royalties from the sale of the coal.

In 1830, the Chamberlaine trustees purchased land in Collycroft known as Mill Close, which lay between land already belonging to the Charity. The was bought from Mr. Peter Ungea Williams for £605.

The following year in 1831, the Mill Bank Charity Colliery, was sunk by Peter Williams. The Chamberlaine trustees invested £3,000 in the new colliery, becoming shareholders as well as royalty owners of the extracted coal. This greatly increased income and helped to provide the funds by which the trustees were able to build new almshouses and schools.

By 1841, ownership of the Mill Bank Pit had passed to Caroline Wilson who entered into litigation over mineral rights with William Wilson owner of the nearby Collycroft Colliery. In the same year, Mill Bank ceased production and the Nicholas Chamberlaine Charity sold some of the land on which it stood, as it now had little value.

Another colliery was later built nearby on more of the charity owned land. This became the Bedworth Coal and Iron Co. Ltd. and was always known locally as The Charity Colliery. The colliery ceased working in 1924, having passed into the ownership of Stanley Brothers from Nuneaton in 1877.

For a more detailed account of these and other pits in the Bedworth and Nuneaton area 'The Warwickshire Coalfield' written by Laurence Fretwell is available at Bedworth and Nuneaton Libraries.

The Almshouses

1840 saw the construction of the present almshouses, the wonderful mock Elizabethan buildings which cost £8,500 to build.

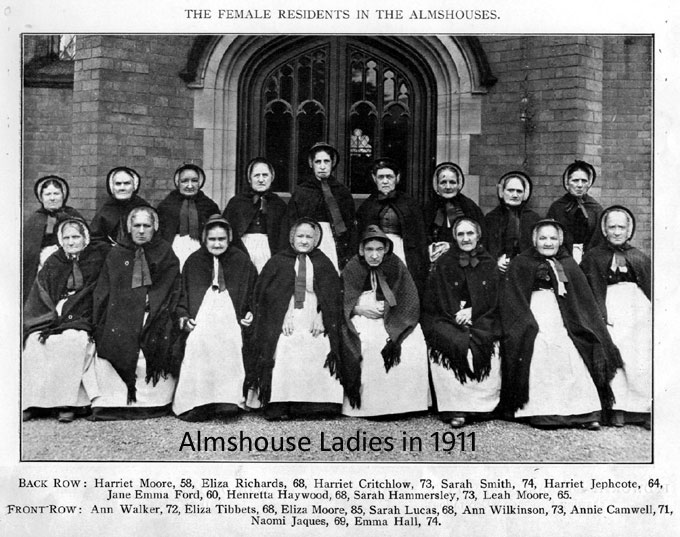

From the opening of the first almshouses in 1715, uniforms were worn by the inmates (not residents) of the almshouses. There appears to have been little change in the fashion of the men’s clothing. The heavy serge material, colour and buttons, etc., remained the same, although breeches probably preceded trousers. For the women, the original straw poke bonnets were superseded by bonnets with less poke, and the reddish-brown dresses gave way to black ones, with red and black plaid shawls, with red cloaks for winter and white shawls for summer. After the First World War there was a further change in the women’s outfit, felt hats replaced the bonnets and a long cope, dark grey in colour was worn. Owing to clothes rationing and high prices after the Second World War, other changes were made and some of the inmates had to wear their own clothes. The wearing of uniforms was discontinued around 1951, but many in Bedworth still remember the old folks wearing the familiar clothes.

The almshouses nearly came to a sad end in the 1970s. The fabric of the buildings was deteriorating due to difficulties in releasing funds from the charity reserves and few people were in residence. There were suggestions that the almshouses should be demolished and the land put to a new use.

A fresh look at the financial position by the Trustees saved the day and the long period of restoring the almshouses began. The final resident's flat was restored only in 2003.

A fresh look at the financial position by the Trustees saved the day and the long period of restoring the almshouses began. The final resident's flat was restored only in 2003.

These magnificent efforts can be seen from All Saints Square in the centre of the town, with the white painted clock tower standing proud for all to see. The Almshouses now provide very high quality sheltered housing to the elderly. It is no longer reserved only for the needy, but is much appreciated by all those fortunate enough to be in residence.

The boundary wall at the front of the Almshouses was rebuilt and repositioned during the pedestrianisation of All Saints Square. The line of the foreboding original wall and railings is now marked merely by black metal studs in the paving of the square.

The residents of the Almshouses enjoyed their Founder's Day dinner until the Second World War, when severe rationing, caused it to be discontinued. However the tradition was revived in 2000 and the residents once again celebrate the vision and legacy of Nicholas Chamberlaine each year.

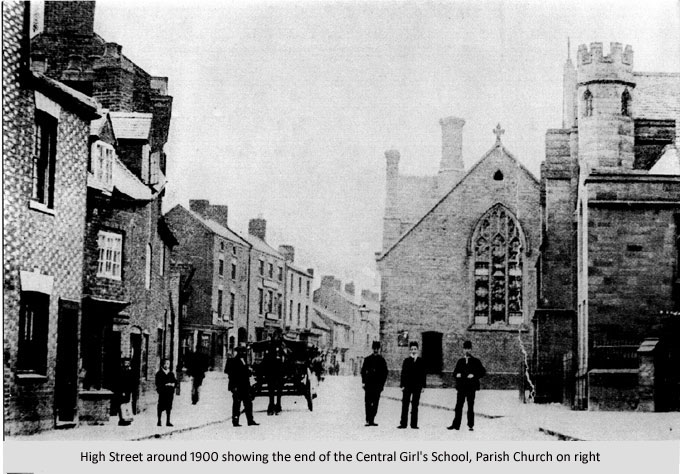

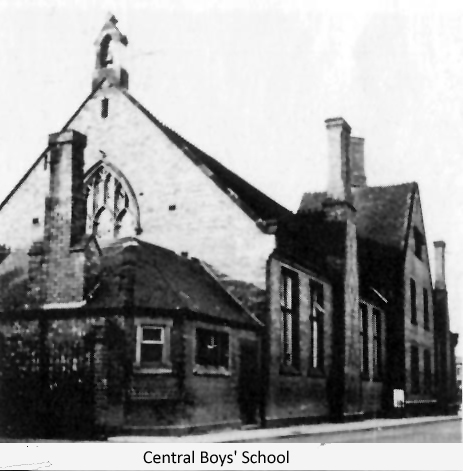

The Schools

The schools were replaced around 1845, being built in the grounds of the old Bedworth Hall, where the Health Centre is today. The Boys' and Girls' Central Schools survived until the early 1960s.

Around 1845, Bedworth Hall, the old schools and original almshouses were demolished to make way for the building of the new Central Schools. These were followed by new schools at Collycroft, Woodlands, Hob Lane and Bulkington Lane, providing education for most of the children of the town.

Bedworth Hall was demolished in 1871.

In the early days of the charity the boys were supplied with a jacket and waistcoat of dark grey cloth with blue collar and cuffs (of the same design and colour as the men’s coats) with brass buttons, which were round and about the size of a ten pence coin. The buttons bore the words ‘Nicholas Chamberlaine’s Charity’ around the outside and ‘Bedworth’ across the centre. Boys also wore a Tam o’ Shanter cap with a blue top-knot.

Girls wore a blue print dress with tippet, a white apron and bib and a white straw poke bonnet with blue ribbon.

The boys had one suit for Sundays and another for weekdays. Every Monday morning they had to take their Sunday suit and leave it at school, fetching it home again on Friday for Sunday wear. The supply of clothing for the children came to an end in 1864 with the retirement as Rector, of the Rev. Canon Bellairs.

Bun Day

At Whitsun all the residents of the almshouses and the school children were provided with a dinner by the charity to commemorate Founder’s Day. The children’s meal was stopped during Victorian times, when the numbers had considerably increased. Instead each child was presented with a bun.

The tradition of Bun Day continues to the present day. The pupils from all the charity schools meet at the Almshouses for a short service on the grass in front of the buildings and each child takes away a current bun. The celebration is always the first event of the mayoral year for the Mayor of Nuneaton and Bedworth and is also attended by the local MP.

The tradition of Bun Day continues to the present day. The pupils from all the charity schools meet at the Almshouses for a short service on the grass in front of the buildings and each child takes away a current bun. The celebration is always the first event of the mayoral year for the Mayor of Nuneaton and Bedworth and is also attended by the local MP.